This article is a part of DailySocial’s Mastermind Series, featuring innovators and leaders in Indonesia’s tech industry sharing their stories and point of view.

John Patrick Ellis, well known in the industry as J. P, is a technology and finance entrepreneur based in Indonesia for the past 15 years. Born in the United States and raised in Asia and Europe, he first came to Indonesia to work in development in 2005 and remains here until today as a fintech founder.

J. P.’s career journey is full of unexpected choices and serendipity. From New York’s legal industry to education and public health work in Flores, associate roles in a regional private equity firm, launching an early location-based messaging application from his Jakarta dining room table in 2012, to helping establish the Indonesian Fintech Association and founding a successful regional fintech company.

With a background in political science, international relations, and languages, J. P. has extensive experience in entrepreneurship, technology and deal-making. In his current role as the CEO of the C88 Financial Technologies group, he oversees a diverse fintech business in the credit decisioning, financial analytics, credit scoring and marketplace lending spaces with over 400 employees in Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Australia and China. We caught up with J. P. to discuss his journey, why Indonesia, why fintech and what it’s like to try and succeed as a non-native immigrant here. Half of our discussion was in English, and the other half in his excellent Bahasa Indonesia, where he expresses himself fluently but with a small accent.

When you were young, did you ever dream to start your own business or become a CEO?

I was born in the United States but I spent my childhood moving every few years around Asia and Europe. This experience of movement and change defined my youth, and has made me a very adaptable, resilient and open-minded person.

As a kid, my dream was to be a competitive swimmer. I trained hard and did reasonably well in competition. But around the age of 16, I realized that I wouldn’t quite make it to an Olympic level. So around that time, I decreased my focus on sport and increased my focus on school and study. But a strong work ethic from swim training has remained with me, and has been a big help to me over the years.

From a young age, I always liked thinking about how to solve problems, but it wasn’t until later in life that I realized I could do that as a founder. So I did a lot of things before I became a founder, but the common thread of my career is a focus on problem solving.

You have background study in political sciences and international relations, what is your actual passion and how does it align with your career?

I like to solve problems, and I like to understand how the world works. I think this is what really drives and defines me. In Indonesia, and all over the world, there are so many problems to solve, and solving problems also creates business opportunities. Not all problems are business opportunities, but many of them are. Many of the world’s great companies were founded this way.

I graduated from Columbia University and the typical next step after studying what I did is to earn a Juris Doctor degree from a law school. Many of my friends did this, and I was intending to as well. After graduation, I worked in New York’s law industry in dispute resolution. It was very interesting and I was very good at my job, but I was sitting at a desk all day. I felt like something was missing. So I applied to several programs for development work around the world. I received many offers including one from Princeton-in-Asia, but the most interesting offer was from a Stanford University-affiliated program called ViA to join a project in Flores, in rural eastern Indonesia.

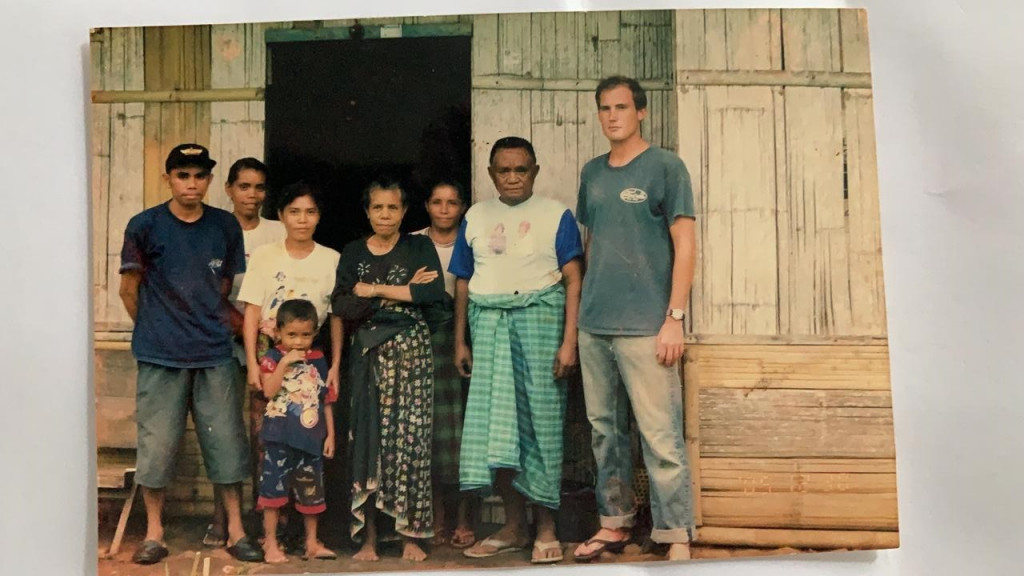

At that time, everything in Flores was very limited. There was no electricity, no mobile phone signal, and no running water. We had to walk through the forest to get to the villages. Perhaps because of this, it was a place of incredible warmth and community. I connected with the Tado people, learned the Manggarai language, and helped bring about some good initiatives in education and public health for the village communities, working with their teachers and their Puskesmas. It was a very fulfilling but also an eye-opening experience.

After that, I worked for very successful entrepreneurs John and Cynthia Hardy, who sold their international jewelry company to a private equity firm. After the sale, John and Cynthia then asked me to help them transform a bare plot of land in Sibang Kaja, south of Ubud, into what is now the Green School; so I was the first employee there. John and Cynthia are so charismatic and so innovative. It was a real pleasure to be around that enthusiasm and energy every day. Through them, I also met my wife Agatha. She also worked there and we met at the team lunch table. We have now been married for close to 13 years and have two young children.

I then had the opportunity to join a regional private equity firm in Singapore and Jakarta founded by Tom Lembong. It was called Quvat Capital and Principia Management. I learned so much from Tom and really enjoyed working for him, Brata, and the team. I spent a little more than four years there and did a lot of varied projects including company due diligence, deal sourcing and execution, fundraising, investor relations, research, special situation restructuring, and even some trading.

Throughout this time, I was really enjoying being around such smart people and working directly with companies in such a dynamic, fast-moving environment. Even though Jakarta is a megacity in many ways it retains the values of a smaller community; its manners and politenesses. I think my time in rural Indonesian villages definitely helped me understand its capital on a deeper level than if I had come to Jakarta directly from New York, Paris, or San Francisco. I think the lesson is that it’s really important to understand things on both a micro-level as well as macro level. You can’t really know one without the other.

Before your current company and CekAja, you founded Harpoon Mobile, are you willing to share some stories about the company?

From 2011 on, I was convinced that the mobile internet will be a very powerful economic force in Southeast Asia. With hindsight, I can see that I was very early in my actions. But I did not realize that at the time. Plus, after several years in private equity, I felt that I wanted to start and grow a business myself. I like creating things and solving problems, I’m very adaptable, and I like challenge and adventure. In many ways, technology startups are the perfect vehicle to express and experience all of this.

We launched Harpoon Mobile from my dining room table, and our first product release was a location-based iOS and Android application called Harpoen. We later added a complimentary product stack called Mapiary, which was basically a location-based ad-server, in an attempt to monetize better.

My co-founders and I liked that we were trying something original. Back then, many startups in the region were likely to be copycat models. We felt proud that we were trying a new idea. Thankfully, many of our friends in the tech community and its media supported and encouraged us. My co-founders and I actually also represented Indonesia at the World Summit Awards for mobile innovation in Abu Dhabi in early 2013, and we won! It was a cool experience to be recognized for innovation.

But innovation alone isn’t enough. Your first startup, the odds are, you will get a lot of things wrong. And that was true for us. In selecting a location as our service core we were locked into the inflexible mathematics of GPS and the complexity of information saturation. To summarize it briefly, in usual information networks content exists on two axes, typically creator and recency or relevancy. Location introduces the third axis and thus achieving a mathematical density of information is exponentially harder: the world is a big place and no matter how large you make the GPS vectors, there will always be places out of coverage and with old content or no content at all. This is the reason a lot of location services like FourSquare and Highlight were not as successful as everyone predicted back in 2012. In the language of computer science, location-based user content would be described as an algorithm with “exponential complexity.”

In retrospect, even if we had been massively successful and achieved hockey-stick DAUs, the commercial model wouldn’t have worked anyway because ad monetization and CPM are commercially very hard to scale in Indonesia even now, let alone back in 2012.

So, after a year of trying — and a lot of awesome experiences including being the first founder to pitch at the first TechInAsia Summit in Jakarta in 2012 — I met a Toronto, Canada-based advertising company who was planning to commercialize location to enterprise clients. Our Mapiary location ad-server could help their clients like Nike take people on interactive jogs, or Heineken takes people on interactive pub crawls. There were a lot of interesting use cases and they were excited about it, and I felt the technology was more suitable for North America as well, so they ended up acquiring what we had built and I was able to return capital to my seed and angel investors. Overall, it was not a resounding commercial success, but it gave me a lot of grit and experience.

How did you come up with the idea of CekAja?

After Harpoon Mobile, I remained very passionate about startups. At that time, the startup community in Indonesia was still quite small and everyone knew each other. I was thinking a lot about what changes and opportunities would be created by increasing economic digitization, and my close friends Sebastian Togelang and Andy Zain were doing the same. In late 2013, we all came together to found Kejora Ventures. I was the founding entrepreneur-in-residence. I started building my fintech company at the Barito Pacific building in Jakarta, side-by-side with Kejora.

We decided to do something unusual and launched in Jakarta and Manila at the same time. It’s quite unusual to launch a product in two countries simultaneously, but we had deep technical resources and strong co-founders like Stephanie Chung in Manila, so it made sense. Plus, fintech in both markets was equally early in 2013; it wasn’t the case that one market was more advanced than the other. So we felt taking a “two birds with one stone” approach would help us scale faster.

We were definitely one of the first companies in Jakarta and Manila to engage with banks about fintech/bank cooperation models. We hit the ground running and visited every bank boardroom pretty quickly. But what we didn’t appreciate back then was how long it would take banks to adapt and change. Even now, I am still amazed that more banks in this region aren’t doing more digitally. This can partially be explained by residual banking-sector trauma from the ‘98 crisis, and that large institutions have incentives that punish failure more than they reward success, whereas startups are the exact opposite. So asymmetrical incentives are my best explanation when people ask me why the pace of change hasn’t been faster. Change is happening though, and COVID-19 has accelerated it.

In the early days, we also realized quite early on that laws and regulations would need to evolve to support fintech innovation. Starting from 2014, I joined with several other fintech entrepreneurs including Niki Luhur, Karaniya Dharmasaputra, Budi Gandasoebrata, Aldi Hariyopratomo, Ryu Kawano, Alison Jap, and many others to start what has now become the Indonesian FinTech Association. We did similar policy advocacy work in the Philippines, too. This created what I think is the momentum for a lot of fintech regulations and activities that we see today in both of these markets.

Over the years, both the business as well as the Association have grown and matured. In the business now, we have marketplace aggregation, marketplace lending, credit scoring, score aggregation, insurtech, data management solutions, analytics, and credit risk management, and decisioning software available in the cloud and as a license. We partnered with Anton Hariyanto, Sulaeman Liong and Rainier Widjaja for enterprise capabilities and our clients are pretty much every banks in the country.

We have an awesome team, and while of course there have been many setbacks and challenges along the way, we are growing and delivering value to our clients and the industry. And in the Association, we have experienced tremendous growth and now there are hundreds of fintech companies in the country, and clear fintech laws, and incredible engagement with OJK and BI. Because of this, I would say that Indonesia has some of the most innovative and clear fintech laws and policies in the whole world. This is the work of a whole industry and I am so proud to have played a small part in it.

You’ve seen the market in some other places, what makes Southeast Asia market different, especially Indonesia?

The region is unique because of its demographics, growth rates, and interest rates. In the region, Indonesia is unique because of its size. The other markets of Southeast Asia each have their own importance, and to be successful regionally there are principles that you must get right to balance the strengths of each market harmoniously versus the weaknesses of others. For example, while Indonesia is large and full of potential, monetization is very difficult and consumers and enterprises are very price sensitive. Other markets may have easier monetization paths, but smaller market sizes and less growth. The best approach for the region therefore creates balance among these elements.

For those who want to start a technology business in the region, I would advise them that the market is fast-moving, and it will remain like this for many years to come. Don’t be intimidated by how fast it moves or think it is “too late” at all. There is now significant internet usage and mobile device penetration, a vibrant venture ecosystem with plenty of capital and professional investors, inspiring leaders and success stories that are locally visible and accessible, there are super apps and also successful exits via both trade sale and IPO, cloud technology is starting to emerge and become viable and this will start to enable SaaS models, laws are clearer, and now COVID-19 has created this massive digitization push. After everyone is vaccinated and the economy opens again, there is clearly going to be an acceleration of tech-enabled business models.

But it’s also important not to start a startup. Instead, start a business. Know your economics, know the path to monetization and profit, focus on doing that well instead of vanity metrics or headline-chasing. It’s sometimes hard to distinguish between these, especially for young founders, and when the media is breathless and boardroom investors demand growth to meet their own portfolio return expectations. But as someone who has done a lot in this space for many years, experiencing both success and failure, I can tell you that you really want to be starting a business and not just a startup.

Entrepreneurship is never easy, especially when you’re not a native. What kind of hardships have you encountered when you first arrived and while building businesses in Indonesia?

Indonesia has been very welcoming to me. It has given me so much and I am thankful for that. I love the work I do every day, the people I work with, and the opportunities we have to solve problems and construct a better industry, a better society, and a more prosperous country.

I think any hardships I have experienced are hardships that any founder experiences: getting to product-market fit, wrestling to be on the right side of unit economics, building a great team and healthy culture, navigating the COVID-19 crisis, and so on. I wouldn’t even call these hardships – this is what being a founder is all about.

In terms of being a foreigner, I honestly don’t even register that anymore. For people who know me well, there is very little friction between my bule self and my Indonesian self. I feel comfortable in both worlds and I like that.

With so much experience in the business, do you still aim for something more in this industry? Have you ever thought of going back to the US for some kind of bottom line?

I’m interested in many things and I feel like I can keep creating new and innovative products and services for many decades to come. There are a lot of things I want to do, and a lot of problems to solve, and new innovations to create.

In fintech specifically, we are still very much at the beginning of the industry. I really believe over the next decade, technology companies will be the ones that harness data, create products, write software, construct analytics, and craft customer experiences to make Indonesian consumers and businesses become universally banked, as well as regionally and globally competitive.

Regarding the United States, I do admit that the country needs to rebuild society and trust and restore its institutions in a post-Trump context. The United States will need energetic and committed people willing to roll up their sleeves and help to do that. I don’t rule out that one day, I might want to go back to play a part in that. But right now, my company, clients, friends, and family need me here in Indonesia and in Southeast Asia. Keep in mind, we also have a significant presence in the Philippines too, and hundreds of employees and a big business there, and there is a lot of opportunity there that I am incredibly excited about too.

About the current pandemic, is there any significant change in your business?

Our clients are banks and financial services institutions. Many were forced to suspend or delay projects and activities due to the pandemic. Even if they didn’t intend to delay things, adapting to work-from-home for such big organizations is a challenge, so many delays are inadvertent. As a business, we have had to be very flexible and adaptive to this reality to ensure we can continue to exceed our client expectations. The good news is that our clients need digital solutions. We anticipate a very encouraging post-vaccine climate for our clients and our business.

Going into 2020, we felt we were as prepared as any company could be for what happened. We have a small executive presence in Beijing, and because of this the executive team and I were aware as early as mid-January of last year that a global pandemic was a possibility. We had scenarios that went all the way up to frightening levels of mortality that thankfully the disease never came close to.

As lockdowns started to happen in the Philippines and Indonesia in March of last year, I gathered the whole company and we laid out a clear strategy of what we were going to do to survive the crisis and ensure business continuity.

We had very specific levels of business continuity, and we sent everyone home to work with clear guidance, policies, and instructions. I also open-sourced our bi-lingual strategy memo and sent it around to many other companies and startups. I wanted what we were doing to respond to COVID-19 to be accessible to others who maybe had uncertainty on whether it would affect them. We thought COVID-19 would create a crisis that would be long and hard and unfortunately, we were right.

Obviously, my team and I were able to make the appropriate changes to the business to put us on a good path. We continue to serve our clients well, are growing profitably, and innovating in our market segments. With vaccines starting to roll-out now, we are beginning to shift to an optimistic mindset for 2022 and beyond. We do feel 2021 will continue to be hard for most of the year, with some improvement towards the second semester.

Something you want to say to those entrepreneurs who wanted to start a business but constrained by pandemic?

I would say It’s never been a better time to start in tech entrepreneurship. Yes, the virus creates challenges but the vaccine is almost here too. Focus on 2022 and beyond. And do not think it’s too late. In technology, it’s never really over because innovation is always innovating versus itself. The code is constantly re-compiling. Yes, it is true that close to 90% of startups fail, but if you focus on building a business instead of a startup, you will already improve your odds of success. Nearly every knowledge you need is accessible and easy to learn. All it takes is the commitment and hard work to do it. I do this, and a lot of my high-performing colleagues and friends do it too. We don’t just magically learn new subjects. Instead, it is a constant effort to stay on top of what is new and be current with technology and the world.

To start a company, you must identify where the big problems are, how do you solve them and how do you turn them into a business. This mindset is something that I spent years learning about and developing. Focus on the problem and the customer, be a learning machine, be both optimistic and realistic at the same time, treat others well, focus on community and you’ll be fine. Indonesia needs more problem-solvers, so you could also argue it is a duty to go out there and solve problems. Kita bisa. Anak bangsa bisa. Saya optimis kok.